Servants on the Kemp Town Estate

In the 19th century domestic England ran on intensive man and horse power, both of which, having reached their peak by the end of the century, were doomed by the 1st World War, the coming of the motorcar and the changes that they brought about.

For the wealthy to live in style took a huge amount of manpower but grand housing developments were built, secure in the knowledge that there was a large pool of labour available to run them.

In 1861 57% of all employed women in Sussex were domestic servants . Women in service outnumbered men by about 20 to 1. This was a period where intense poverty was found side by side with immense riches. A job in service was an opportunity for young people from large families in which they would be not only fed, housed, trained but also receive a wage which could help support their own families. Alternative poorly paid jobs available were mainly in agriculture or in a factory.

Contrary to modern perception, working in service was not necessarily the bed of roses that is often portrayed in the media. Discipline was strict and breaking the rules could mean instant dismissal without a reference. In fact there was a considerable flow of servants coming and going as new (Employment) Agencies opened in the towns.

In the census of 1871, in Chichester Terrace 37 residents employed 71 servants. Nearly every house had at least one butler or footman with the rest of the army composed of widowed or single women and girls. While not every house on the Estate employed a housekeeper, there was nearly always a cook, a number of housemaids, possibly a parlour maid, a lady’s maid and a nursemaid or two if there were small children in the house. Interestingly, in No 2 Chichester Terrace 15 servants looked after just 5 family members, while at No. 7 Arundel Terrace only 4 servants (Cook, housemaid ,nurse ,nursemaid) worked for a married couple and their 11 children ranging from between 23 to 7 years old.

Often ‘upper’ servants came to Brighton with their employers, in particular cooks and ladies maids. However, as can be seen in the Census records people born all over the country, particularly in the southern counties, came to Brighton to find work.

Schools often had a low ratio of servants to teachers and pupils

In the mid to late 19th century there were none of the labour saving devices that today we take for granted, not necessarily even gas or electricity. Light came through the large windows or from oil lamps and candles, and heat from open fires which would have been banked down or extinguished at night.

Like the rest of Victorian society, the servants were part of a strict hierarchy. Their work was very regimented and hard. Working hours were long and time-off very rare. From the butler down to the lowly kitchen maid, each had specific tasks to accomplish.

The Butler

The Butler’s duties included answering the door to visitors, laying the table in the dining room for the family’s meals, serving and presiding over those meals and, with the help of a footman or parlour maid, clearing the table after their conclusion. At the same time he kept an eye on the fires burning in the ground floor rooms.

Below stairs he would often have his own small room or pantry with a sink in which he washed the glasses. He was responsible for the shine on the family silver and it’s safety. There might be a safe or locked cupboard in his pantry in which valuables were kept. These small rooms can be identified today in basements on the Estate.

The knives had to be polished and sharpened by hand or in a patent knife sharpener. Lamps had to be cleaned, trimmed, replenished and if made of brass - polished. Candles had to be replaced. ( candle ends were one of the perquisites or perks of the housekeeper ) My mother, as a child living in a Victorian vicarage near Penrith in Cumberland in the early 20th century, remembered a ‘lamp room’

The butler was also responsible for the wine cellar and the care of its contents. He was expected to have a good knowledge of wine and how to manage it. He would order the wine and might be responsible for paying for it on his employer’s behalf. Wine was often bought in barrels and the butler would be expected to bottle and label it, keeping a precise record of the contents of the cellar.

If there was no footman or valet, the butler also looked after his master’s clothing and that of guests.

He would have worn in the morning and also at luncheon, a high double-breasted black waistcoat (not a low-cut evening one), trousers ‘of any mixed pepper-and-salt description,’ never black, a black tie, and a black dress coat. In the evening he wore all black, with a low cut waistcoat that could be white if he chose, and a white tie.*

The Valet

The Valet attended to the personal needs of the master of the house. Setting up his washing and shaving equipment. Preparing his clothes and helping him dress, and dealing with any other tasks which his master required.

The Footman

First thing in the morning the Footman cleaned the boots and shoes, and all the household silver. He set the table for meals and assisted the butler, answered the door, and attended to various other tasks in the house.

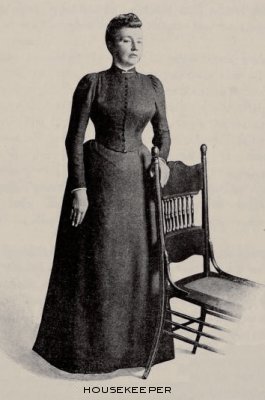

The Housekeeper

The Housekeeper was the principal female servant. As the name suggests she was responsible for the running of the entire house and directed the parlour, house and kitchen maids. She was in charge of the household accounts, tradesmen’s bills, and ensuring that the house was clean. She was also responsible for the servants’ accommodation.

The Parlour maid

The Parlour maid’s work depended on whether a footman was employed. If not, she took on many of a footman’s duties and assisted the butler in the dining room and pantry as well as possibly looking after her Mistress’s person, doing her hair and putting out her clothes if no ladies maid was employed. This would include impeccable mending of tears in delicate fabrics or lace.

She would also be expected to do some of the lighter cleaning tasks downstairs and perhaps arrange flowers around the house and on the dining room table.

Dinner over, the parlour-maid would then have to remove and wash up the plate and glass used, restoring everything to its place; next prepare the tea and take it up, bringing the tea-things down when finished with, and lastly, give any attendance required in the bedroom.

In the morning a parlour maid wore a print gown, a white apron and a plain white cap and in the afternoon a simply-made black dress relieved by white collar, cuffs and cap, and a pretty lace-trimmed bib apron. In most houses servants had to pay for their own uniforms.

In some cases the terms ‘parlour maid’ and ‘house maid’ were interchangeable.

Housemaids

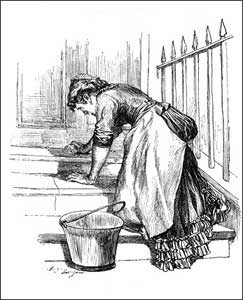

The first job of the day for housemaids was to clean and polish the grates and marble surrounds, lay and light the fires downstairs and probably one or two in the bedrooms upstairs, empty chamber pots and carry quantities of hot water to the bedrooms before the family ventured out of their warm beds into the spartan cold of a windy Brighton day.

Furniture and floors were polished with a variety of waxes probably made on the premises , upholstery and carpets brushed on hands and knees and all surfaces and ornaments dusted before the family appeared downstairs. The front steps would be scrubbed and the surrounding pavement swept clean- every day whatever the weather !

Linen would be changed and the upper floors cleaned once the family was downstairs.

Laundry would mostly be done on the premises in a large copper boiler together with all the intricate starching and ironing achieved with flat irons heated on a stove.

The care of clothing was a constant occupation ( no dry cleaners ) and every process from the careful drying and brushing of wet clothes and hats to the removal of mud and stains from woollen, silk and satin garments with various potions and procedures was a complex art.

The fiction that all this happened by some sort of magic was enhanced in some houses by having an entirely separate servants’ staircase or small ones short cutting from the main staircase to a floor above, these can still be seen in many houses on the Estate. Some now totally cut off or disused. Servants were not expected encounter members of the family unless actively assisting them.

The Cook

The cook both ordered and cooked food for all the inhabitants of the house. The staff would have had a plainer diet than the family although leftovers would have been used up economically. There were no refrigerators as such, although ice boxes were used where possible, meaning that food had to be replenished daily from local suppliers. All the food had to be prepared by hand and several large meals a day set in front of the family. Again, no electric beaters, etc made every task extremely arduous and making the varied and complicated dishes expected upstairs needed considerable time and energy.

There were cooks as old as 64 working on the estate and some as young as 18.

The Kitchen maid

The Kitchen or Scullery maid would have had to clean and prepare all the vegetables and tackle a constant stream of kitchen washing up - in cold water.

Servants were accommodated in the upper rooms of the house or slept in the basement. The housekeeper sometimes had a sitting room next to the basement door where she could keep a strict eye on the comings and going of tradesmen and servants. Contrary to modern perception working in service was not necessarily the bed of roses that is often portrayed in the media. Discipline was strict and breaking the rules could mean instant dismissal without a reference. In fact there was a considerable flow of servants coming and going as new Agencies opened in the towns.

By the early 20th century, wars, the invention of labour saving devices and new employment opportunities for both men and women caused a drop in servant numbers although these tended to increase during economic depressions. In consequence people started to go out to the new cafés and restaurants for meals ( cheaper than employing a cook ?) accelerating the changes. It became an extravagance for all but the biggest houses to have servants.

Domestic service, novelist and broadcaster JB Priestly declared in 1927, was “as obsolete as the horse in an era of motor cars. “

On the Estate is it is clear from the Street Directory records that during and after each of the two World Wars, the population changed dramatically and more and more houses were divided into smaller and smaller dwellings.

In 1881, in No 11 Chichester Terrace, the Hodgson family of 6 people employed no less than 10 servants ! From 1951 onwards the same house is listed as having 18 separate flatlets or flats.

AVERAGE YEARLY WAGES paid to domestics, with the various members of the household.

From Isabella Beeton’s Book of Household Management 1861

When not found in Livery When found in Livery

The House Steward From £40 to £80 -

The Valet From £25 to £50 From £20 to £30

The Butler From £25 to £50 -

The Cook From £20 to £40 -

The Gardener From £20 to £40 -

The Footman From £20 to £40 From £15 to £25

The Under Butler From £15 to £30 From £15 to £25

The Coachman - From £20 to £35

The Groom From £15 to £30 From £12 to £20

The Under Footman - From £12 to £20

The Page or Footboy From £8 to £18 From £6 to £!4

The Stableboy From £6 to £12 -

When no extra allowance

is made for Tea, Sugar and Beer When an extra allowance

is made for Tea, Sugar and Beer

The Housekeeper From £20 to £45 From £18 to £40

The Lady’s Maid From £12 to £25 From £10 to £20

The Head Nurse From £15 to £30 From £13 to £26

The Cook From £14 to £30 From £12 to £26

The Upper Housemaid From £12 to £20 From £10 to £17

The Upper Laundry-maid From £12 to £18 From £10 to £15

The Maid-of-all-work From £9 to £14 From £7½ to £11

The Under Housemaid From £8 to £12 From £6½ to £10

The Still-room Maid From £9 to £14 From £8 to £12

The Nursemaid From £8 to £12 From £5 to £10

The Under Laundry-maid From £9 to £14 From £8 to £12

The Kitchen-maid From £9 to £14 From £8 to £12

The Scullery-maid From £5 to £9 From £4 to £8

Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management 1861

Vanessa Minns