The History of 8 Lewes Crescent

1 Professor Marcus Cunliffe

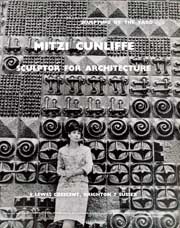

2 Mitzi Solomon Cunliffe

1 Professor Marcus Cunliffe

Marcus Falkner Cunliffe (1922–1990) was a British scholar who specialized in American Studies, especially military and cultural history. Cunliffe stressed the powerful influence of Americans’ cultural beliefs about their own natural military capacity, reinforced by a latent dislike of military professionals, on the nature and performance of the militia/volunteers. Cunliffe pointed the way to the “new military history” in his Soldiers and Civilians: The Martial Spirit in America, 1775–1865 (1969). Cunliffe explored American “exceptionalism” and the national desire it promotes to look inward rather than outward. Cunliffe forcefully argues that the United States was less exceptional than many American writers believe. He always emphasizes the interconnections between Western cultures. Living in Washington in the 1980s, he perhaps reacted against the chauvinism of the Ronald Reagan years; but his writing invariably stressed the European (and especially British) roots of American military ideas.

In 1949, he met and married American sculptor Mitzi Solomon sculptor and designer of the BAFTA award.

2 Mitzi Solomon Cunliffe

As early as 1944, Mitzi had created the first of two marble sculptures — a 32-inch-high (810 mm) winged female figure in red Spanish marble entitled “harp-form” — under commission from Henry Dreyfuss, noted industrial designer, for a new fleet of ships called “4 Aces” for American Export Lines.[5]

Her first large scale commission was two pieces for the Festival of Britain in 1951. One, known as “Root Bodied Forth”, shows figures emerging from a tree, and was displayed at the entrance of the Festival.[2] The second, a pair of bronze handles in the form of hands, adorned the Regatta Restaurant.[3] She created a similar piece, in the form of knots, in 1952 which remains at the School of Civic Design at Liverpool University.[3]

Heaton Park pumping station was built in 1955, for which Cunliffe was commissioned to design and craft a relief panel which depicts the water being brought from Haweswater to Manchester. It has been described as “a remarkable piece of public art on ... a mundane industrial building”.[4] The building was listed in 1998 as a “complete work of art”, the only such listing for any building built after 1945.[2][4] That year, she was also commissioned to create the BAFTA mask for the Guild of Television Producers and Directors.

The Bafta mask, commissioned by Andrew Miller-Jones in 1955. for the then Guild of Television Producers.(Later The British Academy of Film and Television Arts)

Cunliffe originally modelled the mask in Plasticine, from which the casting moulds were made, and though based on the traditional concept of the theatrical tragicomic mask, it is more complex than its immediate front facial appearance suggests. The hollow reverse of the mask bears an electronic symbol around one eye and a screen symbol around the other, linking dramatic production and television technology, and the full intention of Mitzi’s original design included a revolving support to allow the mask to be turned and viewed easily from either side.

She created a large pierced screen for the restaurant at Lewis’s department store in Liverpool in 1957. She bought the piece when the Restaurant closed in 1986, and moved it to her home at Seillans in the south of France.[2][3] She also designed textiles for David Whitehead and Tootal Broadhurst, and ceramics for Pilkington.[2][3]

In the 1950-60s Mitzi Cunliffe developed in Manchester (UK) sculptures consisting of multiple blocks about twelve inches square which she put together in a variety of combinations to give a sculptured effect on a large scale. She referred to them as modular sculptures. Some of these works were acquired by the University of Manchester and the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (UMIST).[7] Interestingly, in the same studio at 18 Cranmer Road, Greek artist Leda Luss Luyken explored a similar principle of variable modularity in the arts in her ModulArt paintings of the 1980s.

Cunliffe developed a technique for mass-producing abstract designs in relief in concrete, as architectural decoration, which she described as “sculpture by the yard”.[3] She used the technique to decorate buildings throughout the UK, but particularly in and around Manchester. One example is a relief panel set high up on the external wall on the 1967-68 modern extension of Altrincham General Hospital on Market Street. Her last major architectural commission was the creation of four carved stone panels for Scottish Life House on Cheapside in the City of London in 1970.

Cunliffe suffered from arthritis and eye problems in later life. She gave up sculpture to teach at Thames Polytechnic (which later became London South Bank University) from 1971 to 1976, and then at the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies and the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum in New York, the University of Pennsylvania, and Concordia University in Montreal.[2]

Notes from Jason Cunliffe

Mitzi did much of her most interesting sculptural work while at 8 Lewes Crescent.

and also developing wider sculptural and architectural ideas, and writing.

She LOVED Brighton, the light the architecture, people, mood, and that house and sea view.

She had grand solo show in London 1969.

The garage space at the back entry of the house was her studio.

I helped her there sometimes. Or just hung out, watched or made things myself.

It was the shortcut on my walk home from school. Which was often a daily trip to hell and back. So arriving home at the door of her garage studio, to find her happy and working hard in smock and dust was a wonderful antidote.

She landed a large stone carving commission, 4 carved limestone panels for an insurance building in The City of London. So had to setup a larger space. She found and quickly renovated a mews garage space just round the corner in back for that project.

Carved with a handheld pneumatic hammer and set of special chisels.

She was happy _while_ she was actually carving, because the tool made it possible to carve closer to the speed at which one “thinks the emergin form” she said.

But it nearly killed her. and she was in increasing nightly pain, with dangerous nerve and bone damage as direct and visible result. She had used the same tools and technique before in 1955, but not on that scale.

By 1970 her spinal and neck vertebrae Xrays show big nasty spurs on them.

Nerve+Bone specialist Doctor told her NEVER to carve anything ever again.

Don’t even think about it he said, “Mrs Cunliffe you risk losing either motor control and/or nerve sensation in your hands and arms”

Then 1971 the marriage ended [badly]. The house was sold, Mitzi moved to London where she started teaching Architecture students at Thames polytechnic, and lectures at Architectural Association, publishing articles, speaking at international confernces.