Despite the uniform width of the houses and the integrated design of their facades, their size and layout is as varied as the speculative builders and private owners who built them. Some added substantial back additions to the main building, others none. There was however a general convention in the layout and use of large terrace houses of the period. From their completion, between 1828 and the mid 1850’s, and their gradual conversion into flats from the early twentieth century, the houses were typically laid out for family use as follows:

Basement: The basement was a service floor, used exclusively by domestic servants. Approached by stone steps down from the street to a front well area, the basement was entered by a door under the front entrance steps, giving on to a vestibule and the long dark corridor to the basement rooms. This was the entrance used by tradesmen delivering food, laundry and household supplies to the house. Under the front pavement were three vaults, one or two of which were used for coal, shot through coal holes in the pavement above.

With ceilings relatively low at 9 foot, the basement rooms in the main building were, at the front, the housekeeper’s room with a commanding view of the steps down to the tradesmen’s entrance. The housekeeper controlled an internal store at the back of her room used for household china or other valuable domestic stores. Behind the housekeeper’s room, the back room was used as the butler’s pantry, again with a secure internal store, used as a wine cellar or alternatively as the plate room, for silverware. The housekeeper and butler each had a sink in their rooms. These rooms were for working as well as sleeping: the housekeeper perhaps mending linen and clothes, the butler cleaning silverware and the family’s shoes as well.

Towards the back of the building, stone service stairs rose from the basement corridor to the ground floor and up through the house. The corridor led on, beyond a central light well, to back rooms with higher (16 foot) ceilings, well ventilated with tall sash windows. Here was the kitchen and adjacent, a room used as the servants’ hall where meals were taken. In the kitchen, the coal range was kept burning summer and winter for cooking and hot water. A scullery projecting into a back well area, used for washing dishes and laundry, had a coal-fired ‘copper’ for heating the washing water. Those houses which had access to the back service street eg Rock Street and Arundel Place, reached the street by stone steps from the back area. Under the pavement at the back of the building were further vaults used for the kitchen’s coal and other non-perishable stores.

Above is a plan of the basement at 11 Lewes Crescent drawn during the Rev Elliott’s tenure there (1854-1875), showing the housekeeper’s room at the front, with its china room and the butler’s pantry behind with its wine cellar, all clearly marked. The kitchen and scullery were at the rear beyond a central well area, with an unidentified room adjacent which may have been the servants’ hall. At the back, service stairs from Rock Street.

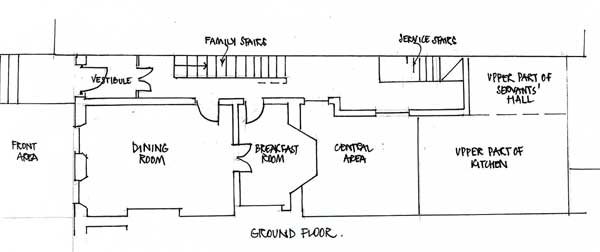

Ground floor: The formal entrance to the house was on this floor. A glazed screen with double doors created a vestibule at the front part of the entrance hall keeping the rest of the house a little more private from callers and warmer when cold sea breezes were blowing.

With ceilings 12 foot high, the dining room was located at the front of the house and the smaller room behind, perhaps a breakfast room, both located just one flight of stairs from the kitchen and service quarters below. At this point, the ground floor did not extend to the back of the house because the very high ceilinged kitchen took up all the space between the basement and the first floor mezzanine level. With the kitchen of only one, high ceilinged, storey, the family’s view from the first floor rear room would have extended over the kitchen roof to the back of the plot. In the case of 22 Lewes Crescent, for instance, this view extended over the single storey kitchen to the family’s garden behind. At No.11 the Rev Elliott could see from his first floor sitting room across to the steeple of his church, St. Mark’s, behind the house on Eastern Road.

The upper floors were accessed by an elegant staircase, of wide and shallow steps, often of stone cantilevered from the party wall to give a clear open stair well to the top of the house, lit by large windows on the half landings. Decorated iron balustrades and a continuous mahogany handrail ascended the house with the stairs. In houses built by Thomas Cubbitt, the family staircase continued in stone right up to the second floor bedrooms giving way to timber stairs only for the final steep and winding flight up to the nursery or servants’ bedrooms on the third floor.

First floor: From the half-landing on the main staircase a corridor led to a back room above the servants’ hall, overlooking the rear. This could be a study or a bedroom. On the first floor of the main building, extending across the whole front elevation was a high (13 foot) ceilinged drawing room with three sets of French doors giving on to a balcony overlooking the gardens. In some houses an enclosed belvedere extended out over a front entrance porch, in others the cast iron balustrade of the balcony supported a canopy over. The drawing room was connected by double doors to a sitting room behind, for use as one space on grand occasions. Both rooms would have impressive slate or marble fireplaces and both rooms had an elaborate plaster cornice and central rose to the ceiling. Visitors would be received on this floor.

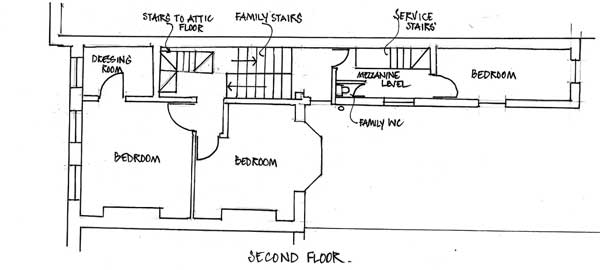

Second floor: From the half landing between the first and second floors was another passage leading to a WC compartment and a further bedroom at the rear. On the second floor of the main building were two family bedrooms, front and back, the front one with a dressing room attached. Ceiling heights here were about 10 foot. Each bedroom had a fireplace but with a more modest fire surround at this level.

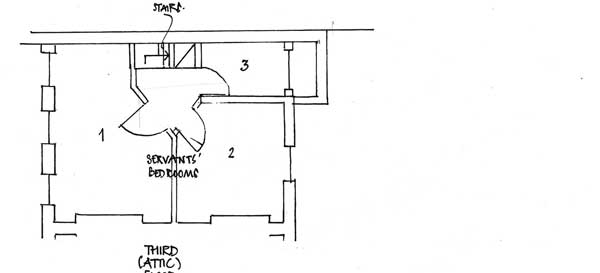

Third (attic) floor: Steep and winding timber stairs led from the second floor landing to the attic floor. Here were three rooms used as a nursery or servants’ shared bedrooms, again each with a fireplace but with smaller, functional surrounds, of cast iron. Ceilings at this level were only 7 foot high and, with no insulation between the lathe and plaster ceiling an d the slate roof above, these rooms could be unpleasantly cold in winter and hot in summer.

Services

These houses were built just as piped drainage was superseding the chamber pot and midden as the way of dealing with ‘night soil’. The drains ran from an outside servant’s WC under the basement stone stairs at the back of the house, under the kitchens to the central well area where the family WC connected from its cubicle on the second floor landing. The drains connected with the estate sewer under the front carriageway.

A water supply was connected to the kitchen and basement WC and to an upstairs WC/wash hand basin but there were no bathrooms as we understand that term today. The supply of water under pressure was, initially, for certain hours of the day only. After 1853 a constant supply of water under pressure was provided.

Hot water from the kitchen range was carried upstairs by servants to wash stands or hip baths in the bedrooms. Coal from the cellars was carried up to each fireplace in use and kept fed with coal while alight. Slops from wash stands and chamber pots, and ashes from the fire grates were then carried downstairs again by servants.

With pitchers of hot water being carried upstairs to bedrooms and slops being carried down again, there was an incentive to separate this traffic from the family and their guests using the main staircase. A separate service staircase with stone treads, lit only by borrowed light and at a pitch steeper than the family staircase, led up from the basement kitchens to the ground floor dining rooms and on up to the first and second floor mezzanine levels. It was positioned along the same wall as the family staircase but further to the rear and issued onto the ground floor and mezzanine level corridors from behind green baize doors.

Servants were summoned to the family rooms by a system of bells pulled by wires running from a point beside each fireplace to a panel of bells in the basement, the distinctive sound of each bell helping to identify the location of the caller, without necessarily looking at the panel.

The rooms were lit by candles and oil lamps, and later by gas mantles and gasoliers, chandeliers lit by gas. Electricity did not arrive until 1887.

Andrew Doig

2016