Corsets, Hats and Whiskers

The style of costume historically developed over time as tailors understood ways of cutting cloth in more and more subtle ways, resulting in more and more sophisticated shapes. The T shaped garment of the pre Norman period thus took about 900 years to turn into the intensely body shaping styles of the 19th century. These shapes altered distinctively during that century before relapsing into the comparatively simple shapes of the 20th century.

For Victorians there were lots of magazines available, including The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine founded in 1852 by Samuel Beeton, publishing coloured fashion plates and multifarious tips on Household Management.

Ladies clothes

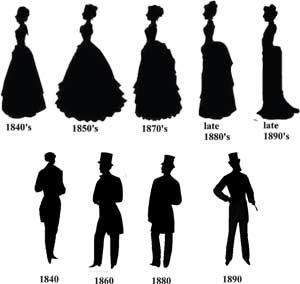

Thomas Kemp started building his new Estate in the 1830’s , however houses were still being completed in the 1840’s - thus although the style of architecture is what is now known as ‘Georgian ’ the inhabitants very quickly were uniformly Victorians with all that implies in their lifestyle. Skimpy little semi transparent dresses with fetching bonnets and saucy parasols would not have been seen in the Gardens for long ! Instead huge skirts and tightly corseted silhouettes would have struggled through the Garden gates ! Men’s clothes sadly, lost the flamboyance and colour that had predominated in the Regency period and became sombre and elegant, never to return to that stunning stylishness as mainstream wear again.

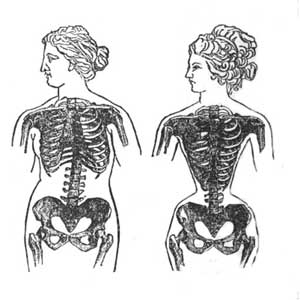

. Women’s’ bodies were laced into hourglass corseted shapes and skirts were so large that they had to be supported away from the body on a frame or crinoline. Both the Press and the medical profession strongly deplored the extreme corset fashions.

Negotiation of stairs and doorways or getting into a carriage was immensely difficult to accomplish gracefully and in fact just sitting down became an art. Less wealthy people wore plainer and simpler versions of what was being worn by the Beau Monde. Servants wore a much less constricting attire but still had to cope with long skirts and petticoats while scrubbing a floor or cleaning a fireplace.

Towards the 1880s, for the fashionable, skirts were looped back over a bustle pad in order to get them out of the way and the shape of a woman’s silhouette became almost like a reverse ‘S’. It should be understood that, as today exaggerated fashion plates show the desired style but people wore the fashions of the time as it suited them.

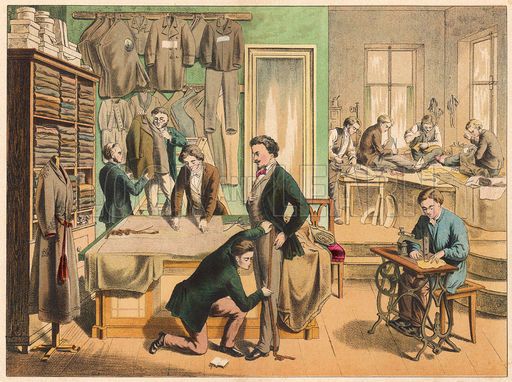

Clothes would be made by a dressmaker or tailor or at home either using paper patterns or by unpicking an existing garment and using it as a pattern. There were dressmakers and tailors in nearby Rock Street. In the 1851 Census report for 10 Arundel Terrace, the butler’s wife Mrs Eliza Knibly, is listed as ’ dressmaker .’

The introduction of the lock-stitch sewing machine in mid-century simplified both home and boutique dressmaking, and enabled a fashion for lavish application of trim that would have been prohibitively time-consuming if done by hand. Lace machinery made lace at a fraction of the cost of the old.

Unlike today, only the really wealthy would own numerous outfits for every occasion though most ladies would expect to change their dress two or three times a day and would have a maid to assist them with buttons and laces. Hats, gloves, tippets, jewellery, shawls, shoes and boots all made up part of a lady’s toilette, all of which had to be meticulously cared for.

As always the dress of the wealthy who were not expected to do a great deal of physical work was extremely expensive and required serious maintenance.

Garments made of natural fibres, wool, cotton or silk were cleaned by brushing and sponging and then pressed. Underwear would be washed, starched and every frill and tuck carefully ironed. Boots and shoes would be cleaned and then polished.

Caring for the clothes of a wealthy man or woman would take a great deal of time and expertise.

Moths were a constant threat ( thriving on not very clean fabrics) and there were numerous anti moth substances to be either purchased or manufactured at home. These included the use of mothballs containing naphthalene, cedar or sandalwood and lavender.

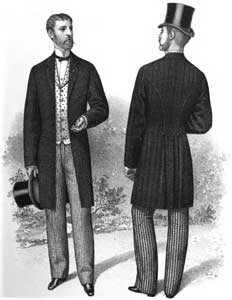

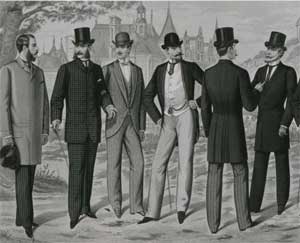

Men’s clothes

Men’s clothes became dark and formal in the 19th century. Frock coats, waistcoats and straight trousers with boots or shoes succeeded the buckskins, pantaloons and hessians of the colourful Regency period. Dark cravats began to supplant impeccably tied neckcloths, whiskers and and top hats arrived. Black was de rigueur for evening wear. Towards the end of the century more casual garments for special pursuits were worn - shooting, boating or even just walking.

Gradually the nipped in waists disappeared and the silhouette of a man became straighter and ever more sombre.Frock coats still had plenty of fabric in the skirt but that too became more an more simple until it almost disappeared, being worn by older men, bishops and at the last by hotel doormen !

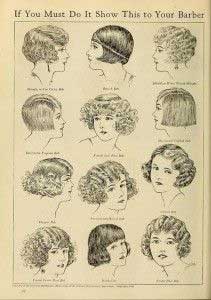

Hats were de riguer for both sexes. Women’s hairstyles, laboriously achieved with curl papers or rags worn at night and the application of hot curling tongs straight from the fire, echoed the shape of their clothes.

Men’s whiskers developed from the neat sideburns of the Regency period, became longer and larger and were joined by moustaches. Towards the end of the century huge amounts of facial hair became the norm.

Men’s clothes were obtained from tailors although shirts and nightwear might be made at home.

In 1875 Arthur Lasenby opened his shop ‘Liberty’s ’ in London’s fashionable Regent Street. In 1884 he introduced a clothing department. The style of the garments was heavily influenced by the Pre Raphaelits and the Arts and Crafts Movement and was intended to challenge Paris as the sole arbiter of fashion. The clothes were simple and loose fitting by comparison with the rigidly corseted shapes current worn but it took another twenty or thirty years before women felt able to abandon their corsets.Older women,in fact,were still wearing them into the 1950s and 60s albeit much less fiercely boned.

The New Century.

By 1905, clothing was increasingly factory-made and often sold in large, fixed price department stores. Custom sewing and home sewing were still significant, but on the decline.

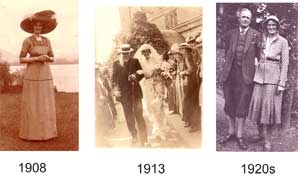

Life after Queen Victoria and the Great War changed completely. Servants almost disappeared and households grew smaller in consequence. Restaurants, tea shops and theatres drew people out in the evening. Music too attracted young people out to night clubs and dance halls. Heavily boned corsets were replaced by bust bodices and later in the century the revolutionary brassiere. women’s legs, hitherto unmentionable, were unveiled below the knee as can be seen in the progression of styles above.

Sport for both men and women needed special clothing and wardrobes started to expand.

Men’s clothes too became less stiffly tailored, ties arrived and various kinds of shoe replaced the ubquitous boots. The final break with the past came as women bravely cut off their long hair and appeared ‘shingled’.

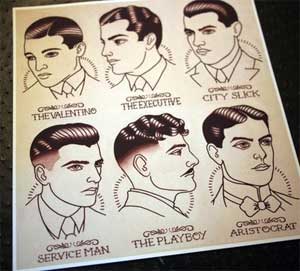

Men shaved off their whiskers and wore their hair short with a neat ’ parting ‘.

21st Century

There is no doubt that the original inhabitants of the Kemp Town Estate, wrapped in their layers of cotton, linen and woolen clothes would have been shocked to the core had they been given the chance to see the clothes worn around their streets today. Women and girls wearing leggings and tops looking like Victorian underwear might have struck them dumb ! There is no doubt that Fashion as a developing story has lost its way somewhat since the advent of the miniskirt and Swinging London. Possibly the most significant fashion arrival in the last fifty years has been that of central heating, jeans, the use of blue jean fabric and the use of cheap labour in the far East. Looking at a crowd of people anywhere, blue jean predominates.Sadly sartorial style has gone into abeyance for most people and in my opinion, our Estate is the poorer for it !

Vanessa Minns