The History of 2 Chichester Terrace

1 Thomas Hatchard and Elizabeth Hatchard

2 William Louis and Marie Ann Winans

3 Charles and Euphrasie Diggings

4 Stanley and Emily Lutwyche

5 St Mary’s Hall (Babington House )

6 Bas Relief

1 Thomas Hatchard and Elizabeth Hatchard: 1854 - 1860

The first occupants of 2 Chichester Terrace from around 1854 were Thomas and Elizabeth Hatchard. Thomas was born in London in 1794 and was the son of the bookseller and publisher John Hatchard, the founder of London’s oldest bookshop, which he established in 1797. At that time, John was a young bookseller who had been plying his trade in the literary coffee houses of London since his youth.

Hatchards has occupied its current building, 187 Piccadilly, since Georgian times. Thomas took over the business from his father, who died in 1849 at the age of 80. The 1851 census shows Thomas and Elizabeth lodging at 6 Belgrave Terrace, Brighton, perhaps whilst they were looking to acquire a substantial seafront house in Kemp Town. Thomas died at 2 Chichester Terrace on 13 November 1858. His will left effects valued at nearly £50,000. His wife Elizabeth died in 1862 at Lausanne, Switzerland and both are buried in St Andrew’s Church, Hove. Their daughter Anne was living as a widow at 8 Goldsmid Road, Brighton in 1881, and described her occupation at the time as publisher.

2 William Louis Winans

For the 37 years from 1860 to 1897, Nos 1 and 2 Chichester Terrace were rented year round by William Louis Winans, an eccentric and exceedingly wealthy American entrepreneur. He, his family and entourage of servants lived here for part of the year.

William Louis Winans was born in New Jersey in 1823, moving to Baltimore about three years later. His father was Ross Winans, a celebrated inventor, engineer and highly successful builder of railroads, who became one of America’s first multi-millionaires. He and his brother Thomas followed into their father’s business, learning the trade in the Winans machine shops in Baltimore.

When the firm Harrison, Winans and Eastwick won a contract to equip the new railway between Moscow and St Petersburg with locomotives and wagons, Ross sent his two sons to Russia, where they established workshops in Alexandrovsky, near St. Petersburg. William met and married Marie Ann de la Rue, later described as the “very mildest and charitable woman”, in St Petersburg, where their sons Walter and Louis were born. Marie was from the same family as the Guernsey printer Thomas de la Rue, founder of the eponymous banknote printing company.

When the railway was completed in 1850, Thomas Winans returned to Baltimore with his Russian wife, whilst William stayed on to see out existing contracts and negotiate new ones. Referring to their success in Russia, an American newspaperman wrote in 1858: “These gentlemen have accumulated, in a few years, almost fabulous fortunes, and their contract holds good for several years to come. The terms are immensely in their favour, and it is said that the Government has offered them a very large sum to cancel it, but the proposition has been refused.” New maintenance and supply agreements prepared by William with the assistance of corrupt Russian bureaucrats opened further opportunities for draining the Imperial Treasury. Finally, in 1868, the Russian government bought out the contracts in return for a huge compensation payment to the Winans family.

William was well known for spending his wealth lavishly to provide for the comfort of his family and in social enjoyment. He once bought up all of the seats to a performance by a large travelling circus and compelled the performers to put on the entire show for the benefit of himself and two friends. His favourite method of entertaining friends was to give morning concerts performed by famous operatic stars, sometimes with half a dozen celebrated vocalists at the same entertainment. Once he professed that he could not enjoy anybody’s music except that of the acclaimed soprano Adelina Patti, and at her first appearance in St. Petersburg he paid $1,000 for the first choice of boxes.

By the autumn of 1859, William’s health broke down. He had symptoms of consumption, and he was warned by his doctor that another winter in Russia would probably be fatal. He was advised to winter in Brighton. Reluctantly, under medical orders, he left St. Petersburg and spent the winter at a hotel in Brighton, returning to Russia when the winter was over. William was obsessed with his health, nursing and tending it with extreme devotion. He took his temperature several times a day, and had regular times for taking his various waters and medicines.

In 1860 he rented No. 2 Chichester Terrace as a furnished house for a term of five years, determinable at the end of any year. He also took the neighbouring house, No. 1, for a term of twenty-one years, determinable at the fifth, seventh, or fourteenth year. He connected the two houses structurally.

William’s name appears crossed out on the 1861 census for the combined houses No. 1 and No. 2, with seven servants living in the properties. The census of 1871 shows William and Marie Ann living at Nos 1 & 2 Chichester Terrace with their sons Walter and Louis, a niece, Celeste Winans, and 15 servants.

From 1860 to 1870, William used to spend the winter at Brighton and about eight months of the year in Russia. In 1870 he gave up his house in St. Petersburg, and took a lease for a shooting estate in Scotland, which led to him becoming popularly known as the “great American deer-stalker”. From 1871 to 1883 he spent about two months in Russia, two or three months in the health resort of Bad Kissingen in Northern Bavaria, and the rest of the year in Brighton, Scotland, or London, where he lived at 23 Grosvenor Square. In 1877, supposedly to please his wife, he bought the Crown lease of 15 Kensington Palace Gardens, and the family were living here at the time of the 1881 census. In 1883 he ceased to visit Russia, thereafter dividing his time between Bad Kissingen, Brighton, London and Scotland.

William’s eccentric disregard for money is illustrated by the story of a $50,000 Axminster carpet he had made from special designs for the drawing room in Kensington. When it was laid, he was disappointed, so he ordered another in a different design. When the second carpet was delivered, the question arose as to what was to be done with the one already on the floor. “Just put down the second over the first,” he said.

William now embarked upon an experiment in the management and improvement of deer forests in Scotland, taking vast tracts of land and enclosing them with miles of fencing to prevent the deer straying. He had developed the notion that the value of the forest for letting purposes would be much increased by suspending shooting for some years, allowing the stags a longer term of undisturbed life. By 1887 he was the tenant of nearly twenty sporting estates in Scotland, the total area of which exceeded 220,000 acres. They constituted a shooting range extending 60 miles from the east to the west coast of Scotland, from the Bealy Firth to the Atlantic, with annual rent payable of about $125,000. At this time, he acknowledged that his annual income was between $2 and $3 million. The experiment led to trouble both with the crofters and with his lessors and eventually he gave it up, believing it to have been a waste of money. He seems to have got rid of all the Scottish shoots before his death.

At the time of the 1891 census, William, Marie Ann and Louis were living in No 1 Chichester Terrace, with no less than 21 servants living in No 1 and No 2. His son Walter and his family and servants were living just down the road at No 7 Chichester Terrace.

William did not live in Kensington Palace Gardens after 1892. It was shut up, and he tried to dispose of it, but he was still listed on the electoral register for the property at the time of his death. He moved his London residence to 10 Pembridge Square in Notting Hill. After 1893, he spent the whole of the year in England – in London, Brighton, and the country. He never bought an estate in England for himself or for either of his sons. As far as he was concerned “he preferred living in furnished houses or hotels”, according to his son.

William never forgot the terror of the chronic seasickness and near shipwreck which the brothers experienced on their first visit to Russia, and the thought of a return sea crossing to the United States appalled him. In a letter responding to an invitation of an old Baltimore friend to visit him, he wrote; “I would not cross the ocean for $5 million cash.”

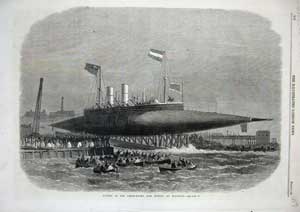

William became engrossed by the design and construction of spindle-shaped vessels commonly called cigar ships, an invention of the Winans family. Details of the Winans cigar ships can be found at http://www.vernianera.com/CigarBoats.html. Many patents were taken out for this design both in England and in America. It was claimed that vessels of this type would be able to cross the Atlantic without pitching or rolling. In an application to Congress in the year 1892, William described the vast benefits that would result from the invention to the people of the United States. He declared his confident expectation that a fleet of spindle-shaped vessels subsidised by Congress would restore to America the carrying trade which had fallen into the hands of England and other foreign nations, secure to America the command of the sea, and make it impossible for Great Britain to maintain war against the United States. Such a fleet as he described in his application could, he said, “meet war vessels in open sea near the European side and destroy one vessel after another, so that none of them would be able to reach our shores.” In the development of his invention William stated that he had incurred an expense of nearly $4 million in the research and development of four full sized prototypes. His confidence in this project remained unshaken to the end of his life, and he kept an office in Beaufort Gardens, Knightsbridge, where a staff of engineers and draftsmen was engaged in working out the various problems with the design. Perhaps he pinned his hopes of returning to the United States on the eventual success of the invention, which was to prove elusive.

William Winans was said to be a person of considerable ability and of singular tenacity of purpose, self-centred, and strangely uncommunicative. He was not interested in many things, but he became completely absorbed in a scheme when he took it up. He lived a very retired, almost a secluded life. He took no part in general or municipal politics. He rarely went into society. He had no intimate friends, if, indeed, he had any friends at all in England. There is no evidence that he was interested in any charity or charitable or philanthropic institution in England. Although he was on affectionate terms with his two sons, he never let them into his secrets. “He always worked his business himself,” his son said, “and never brought us into the business affairs in any way.” And although at odd times he mentioned his property in America, he never allowed even his eldest son “to understand much about it.”

William was described in his obituary in The New York Times as a bluff, liberal-hearted man, but thought to be quite un-American in his tastes and disposition. He was said to be averse to having either of his two sons go to the USA, and consequently they developed so called “anti-American tendencies”. His son Walter competed for the USA, winning medals for shooting in the 1908 and 1912 Olympics, but did not visit that country until the age of 58. William was described as particularly anxious that his sons Walter and Louis should marry titles, but neither of them could be persuaded to make any of the matches that were available. Walter married Caroline Rowland Belcher, daughter of a Brighton physician, in Brighton in 1881 and it appears that Louis did not marry.

William held both houses in Chichester Terrace at the time of his death – the furnished house, No. 2, as tenant from year to year and No. 1 on a tenancy similar to that on which it was originally taken. He died on 22 June 1897 at Pembridge Square in Notting Hill, leaving an estate in Great Britain valued at £2,522,005 17s 1d.

His sons continued to live in Brighton and London. Walter Winans, author of several books including “The Modern Pistol and How to Shoot It” (available at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/41610/41610-h/41610-h.htm), won the revolver championship in England twelve consecutive times and the duelling pistol championship in Paris in 1909. He was a competitor in the Olympic Games at London in 1908 for the United States team, winning gold for the Double Shoot Running Deer. As a huntsman he held records in stag and wild boar shooting. At the Vienna Exposition in 1910 he won two gold medals for the most representative group of big game shot by one man, his exhibit comprising 60 of the best heads of all kinds out of 2,000 he had shot himself. Walter was also a noted artist and sculptor of animals – he won a gold medal for sculpture at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics in addition to his silver medal for shooting won at the same games. A summary of his achievements can be found at http://www.rickeyre.com/blog/node/2351.

Louis William Winans maintained a house at 5 Grand Avenue in Hove, where his mother lived at the time of her death in 1904. With the fortune he inherited from his father, Louis acquired an extremely valuable collection of spectacular coloured diamonds, many through his Brighton-based jeweller, Lewis & Sons, including the historic 31.40 carat pink diamond known as the Agra.

3 Charles Diggings and Euphrasie Diggings

The 1901 census shows Charles Diggings, born in Battle, East Sussex and his French wife Euphrasie lodging in 2 Chichester Terrace. Both were aged 48, he a ladies tailor and she a caretaker. They had two sons aged 14 and 12 living with them.

The question arises as to why a small family of modest means would be the sole occupants of 2 Chichester Terrace at the time. The adjoining House 1, to which House 2 had been connected, was occupied only by a housekeeper and a manservant. The relatively recently widowed Marie Ann Winans was now living in Grand Avenue, Hove with her younger son. Perhaps Charles Diggings was her tailor and she had offered the empty property in Chichester Terrace for him and his family to live in temporarily.

4 Stanley George Lutwyche and Emily Lutwyche: 1900s – 1932

The 1911 census shows that by that time, 2 & 3 Chichester Terrace had been combined into one house and were occupied by the retired leather merchant Stanley George Lutwyche, aged 66 and his heiress wife Emily, aged 62. Their two unmarried daughters Violet, aged 36, and Vera, aged 24 were also living in the houses along with seven servants and a lady’s companion.

Biographical details of the Lutwyches are provided under 3 Chichester Terrace.

Stanley died in 1919 and Emily continued to reside in the two houses until her death in 1932.

5 St Mary’s Hall (Babington House): 1934 – 1970

In 1934, 2 & 3 Chichester Terrace was acquired by St Mary’s Hall Girls’ School to become the boarding house known as Babington House. It remained such until around 1970, when the properties were converted for use a residential flats.

.

Andrew Mosely